Fast Fashion, Is It Worth It?

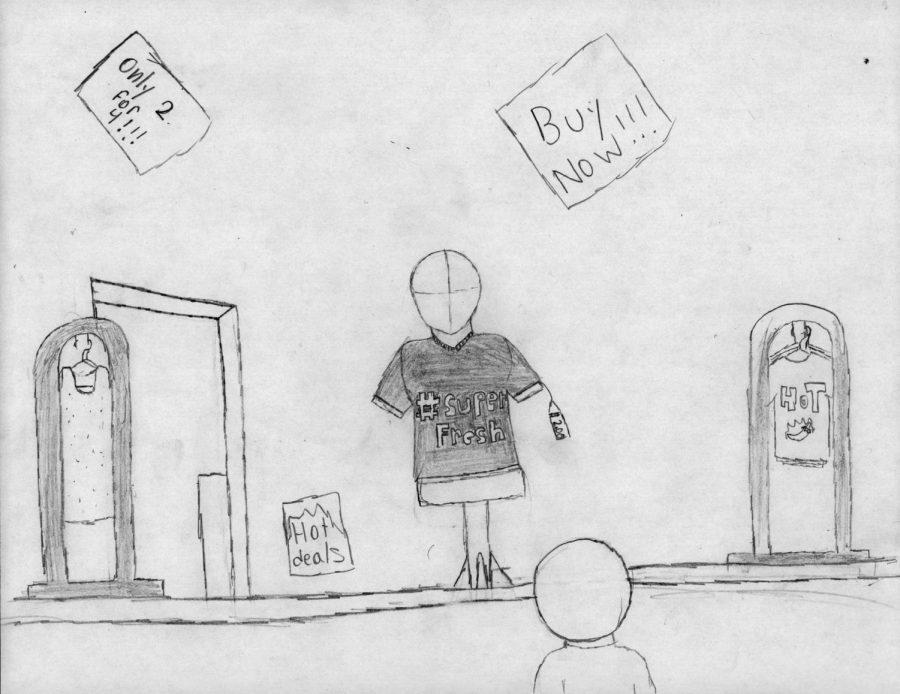

We are lured by the promise of inexpensive clothing, but at what cost?

February 4, 2022

Have you ever bought a $5 t-shirt? A dress that’s labeled “Made in Vietnam”? Literally anything from Forever 21?

Well then, you might be unknowingly contributing to fast fashion.

Consumerism is one of the most defining features of American society, and fast fashion is a prime example of that.

Let me backtrack a little.

As a disclaimer, I’m not going to be mentioning any figures, as many of them are inconsistent, outdated, and/or focused on a specific region rather than the world as a whole. Combined with the research behind them that is extremely lacking, I found that it would be easier to leave specific numbers out.

For those who don’t know, fast fashion is defined by Merriam-Webster as “an approach to the design, creation, and marketing of clothing fashions that emphasizes making fashion trends quickly and cheaply available to consumers.”

This business model enables companies such as Fashion Nova, Pretty Little Thing, Shein, Missguided, and even some makeup brands (*cough* ColourPop *cough*) to appeal to consumers worldwide with the newest styles for the lowest prices.

However, with its promotion of overconsumption, and its unsustainable, unethical production methods, the fast fashion industry leaves much to be desired.

I don’t want to pull a “back in the day,” so I won’t, but online shopping has very obviously changed our shopping habits, and not always for the better. Yes, things are often more affordable, and the ease of clicking on an ad and getting something sent directly to your door is addictive, but often the purchased item is unnecessary and ends up largely unused.

The same is true of fast fashion. Many of the clothes remain mostly unworn, and eventually end up in landfills. Excess inventory, an issue prevalent in all fashion brands, is even more so in companies that specialize in overproduction.

While online shopping had been a pastime from the start, now it has extended to become even easier. As easy as clicking on an Instagram ad.

Ads are everywhere, which is another contributor to fast fashion consumption. Promotions of companies you’ve never heard of, of questionable quality that makes you look at the reviews, are a byproduct of how insatiable we are, never truly satisfied with all that we have and susceptible to buying what is being advertised to us without a second thought as to how it’s made or who it’s made by. Just because something is cheap and/or trendy doesn’t mean that it’s worth the space in your closet.

Influencer and celebrity based marketing practices are another driving force, as some people may see, say, a Kardashian (or another person they follow and admire the style of) wearing a specific top, and will want to wear the same thing or an item resembling it. A plethora of these businesses also send PR packages to influencers who can then promote the company, spreading word of its existence and quality.

Social media also decreases the lifespan of microtrends, which are trends that quickly gain popularity before losing it just as quick. (We’ll circle back to that later.)

All of these factors add to the conditioning we go through as buyers to purchase things that we see other people wearing and enjoying, and worry about the repercussions later.

Inadvertently supporting the industry is hard to avoid, due to the size inclusivity and cheap prices not found in sustainable, ethical fashion. But going to thrift stores and avoiding buying into microtrends—as well as buying clothes you can wear and wear often—can make the practice less wasteful, and the environment we live in more healthful.

Regarding sustainability, products produced by these companies often sacrifice quality for quantity, using cheap, non-environmentally friendly fabrics like polyester and nylon, which are commonly derived from petroleum and aren’t biodegradable.

Extreme amounts of water and pesticides are used to grow cotton en masse, and the chemicals and dyes used during clothing production can prove harmful to both consumers and garment workers.

Speaking of garment workers, many of the clothes sold by these companies are outsourced, made in China, Vietnam, India, or Bangladesh (among other locations), where the people work in sweatshops, oftentimes experiencing abuse while there.

To get the prices down to be as cheap as they are, production costs have to be lowered. Children and women are often the ones taken advantage of in the supply chain, as they’re the most vulnerable. There aren’t any unions to advocate for children because children aren’t supposed to be working in the first place, and, as seen as far back as the industrial revolution, women can often be overworked and underpaid sources of labor in the textile industry.

And that’s not even mentioning the greenwashing and stealing of designs made by smaller businesses, as well as the general opacity of these brands.

So where does consumerism come into play?

As I mentioned earlier, fast fashion allows people to purchase the newest trends for cheap, and because of the rise of platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, things have been in style for a lot less time. Influencers and celebrities (the Kardashians in particular) are the cause of this, and brands have to release clothes much faster in order to profit while that specific style is still relevant.

Typically, fashion brands release two collections: one for spring/summer and one for fall/winter.

Many fast fashion brands have 52 collections a year, or one a week.

Here’s what happens:

We like the new trend (or we don’t want to be left out), we buy said new trend, the market becomes oversaturated with multiple different copies of the exact same trend, and it goes out of style.

And the cycle repeats.

Over.

And over.

And over again.

The rise of online shopping started the fire, and social media fanned the flames.

But social media is also lending itself to the spreading of information about sustainability, smaller businesses that are more ethical, and alternatives to supporting the fast fashion industry.

And that must count for something, right?